ProVeg’s New Food Hub talks to Iain Tolhurst about the benefits and challenges of Organic Stock-Free farming

Without farmers, our food system would collapse. And yet, our food production and consumption system, as many of us know, is already failing. Not only is it promoting food insecurity, but it’s also facilitating the spread of zoonotic diseases.

However, more and more farmers are seeing the opportunities available in Stock-Free Organic farming (organic fruit and vegetable farming, without the use of animals). This, in line with the growing numbers of flexitarian and reducetarian consumers, offers hope for the future.

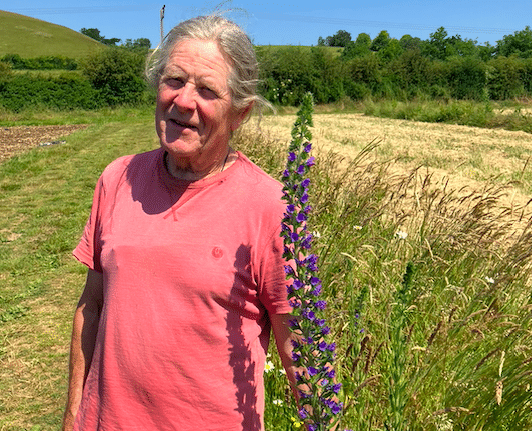

To gain some first-hand insights and key actions for farmers, we caught up with transitioned farmer, Iain Tolhurst of Tolhurst Organic, based in the UK.

Listen to the audio interview, now! Or read the highlights below.

Great to meet you, Iain. Please give us some background on Tolhurst Farm. When did you transition to Stock-Free Organic farming and why?

We’ve been running on this site for almost 36 years, and we’ve been organic right the way through. In fact, I’ve been an organic commercial grower since 1976.

I spent four years on a dairy farm during the early 70s, and that was not organic. But that was a really useful experience; it taught me a lot about commercial farming. And it taught me what I didn’t want to do.

That was my initiation really – four years on a dairy farm and looking at how badly the farm was treated in terms of the soil – the cows were not badly treated, because they were very well treated. But you know, it was the whole system I didn’t like. I didn’t want to be a part of that and became vegetarian and then later, vegan.

I’ve been assisting farmers for nearly 36 years. As I said, Tollhurst Farm has been organic right from the start, and we’ve been Stock-Free Organic since about 2005 – and that is an official set of standards in addition to Organic. We were the first farm in the world to have this standard.

I worked at the Vegan Organic Network and the Soil Association on developing these standards. So, we were the pioneers in this. There are other farmers doing it now – they’re mostly relatively small-scale, but we’re now getting interest from larger farmers who are quite keen to give up their livestock and move on to something else, which is encouraging and we’re in a position to support that.

It’s so encouraging to hear that you’re getting interest from larger farms, as well as smaller ones. With this, please tell us a little more about what Organic Stock-Free Farming entails. What criteria must a farm meet to qualify?

Well, firstly, we have to meet all the Organic criteria, which is a set of international standards.1 So that’s the first part of what we do, then, the additional part to that – the Stock-Free Organic standards – is really about making sure the farm isn’t in any way exploiting animals.

We’re not allowed to keep livestock for gain; we could keep cows if we wanted to, but we wouldn’t be allowed to slaughter them or take milk or anything from them. So it’s not about completely being free of animals but we don’t have any domestic animals on the farm.

It’s also about refraining from using any of the products from livestock farming for agricultural purposes. So, for instance, we don’t use fish, blood and bone, which is a common fertilizer. We don’t use wool for mulching, and we don’t grow food directly for feeding to livestock.

We’re also not allowed to kill or trap any wild animals on the farm, and that includes insects. We have to use natural, biological methods of pest control. So, we encourage predatory insects, rather than killing things with sprays. And there are additional standards and details involved.

Now, to apply to become a Stock-Free Organic farm, you don’t need to be plant-based yourself. It’s not about the personality of a farmer. I happen to be a vegan, but I could be a meat eater and run a Stock-Free farm. It’s all about the farm.

What are the benefits for farmers for transitioning to Organic Stock-Free?

There are lots of benefits, the main one being that the farm is much more self-sufficient, so, not dependent on external forces, like bringing in external fertility. The farm works more within its own boundaries. If it’s done properly, Stock-Free Organic also means you have no problems with weeds, pests and diseases like conventional farms.

In terms of profitability, there is no additional profitability. But if you were to compare our farm, which is quite small – only 10 hectares, with a 10-hectare livestock farm, the 10-hectare livestock farm would not be viable or profitable. The livestock farm would be a very part-time job and wouldn’t provide even more than a very part-time income. We employ a lot of people on our farm, so it also increases employment.

Plus, it’s much better in terms of encouraging biodiversity. So much data has been collected from our farm; it’s one of the most heavily monitored in the country. We have decades of data on our insect activity – we know how many earthworms we have, the number of beetles and how far they travel.

So we’ve been able to demonstrate over many years that our farm is very productive. It produces a lot of vegetables, without resorting to importing fertility from elsewhere and we haven’t resorted to damaging animals in the process.

The main gain is not a financial one. That’s not why people would be doing this; people will be doing this primarily for practical or conscience reasons. Livestock production in the UK is, in many cases, failing badly. There are awful problems in livestock at the moment – disease, for example, and lack of viability.

You now have to have at least 1,000 sheep to try and make a very small profit. It’s got really bad. And I think people now realize that livestock numbers are going to have to drop dramatically if we’re going to try and rescue what’s left of the planet’s biodiversity.

So, our system is more robust – we don’t have the lack of resilience that many conventional farming systems have – we are able to weather quite difficult, well, weather for want of a better word! We’re also very low in terms of how much energy we use, and our carbon footprint is exemplary.

Can such practices be scaled up? As you said, your farm is quite small, but can the practices be done on a much wider, global scale?

Yes, I think there’s no economic reason why it can’t be done. There may be some social reasons why it may not be desirable, like misunderstanding from the local farming community. But in terms of the practicality of agronomics, there’s no reason at all.

I mean, if I could find a farm of 1,000 hectares, it wouldn’t be a 1,000-hectare field, it’d be lots of small fields because one of the things that is really important is our connection to biodiversity. And in order to get that connection, we need to make fields small and put in lots of hedgerows, beetle banks and field margins, which makes it slightly less efficient in terms of machinery used. But it does improve the biodiversity to the point where, as I mentioned, we don’t get the pests and disease problems that you normally get. So there’s no reason at all why it couldn’t be scaled up.

The only inhibiting factor at the moment is a lack of demand for fresh produce. Fruit sales in the UK have been declining by 1% a year for the last 20 years. And that 1% is because people are increasingly eating out. So this is the figure for purchasing fresh fruit and vegetables – in the last 20 years, we’ve lost 20% of sales. And this goes for all farmers producing fruit and vegetables.

If you were to look at the area of agricultural land in the UK, which presently grows fruit and vegetables, it’s less than 1%. It’s a tiny area. If people were to double their fruit and veg consumption – which they should in terms of health – the land would still only be just over 1% of the total land area. That is how efficient feeding people with fruit and vegetables is – it doesn’t take a lot of land.

And if you were to remove most of the livestock in the UK – because 65% of all cereals grown in the UK are fed to livestock – it would release huge amounts of land. This could potentially be used for a whole range of other agricultural activities. Some would be growing crops directly for humans, as well as big fiber crops, and building materials. There are so many opportunities for farmers to diversify away from livestock systems.

What practical and financial support is available for farmers that want to transition to Stock-Free Organic?

It depends on the size of the farm. We’ve not received any support because we’re a relatively small farm. There is no difference in the support mechanism depending on whether you’re a Stock-Free farmer or whether you’re a conventional, chemically inclined farmer – the levels of support are the same.

The difference is, because we are Organic, we will get – from next year – extra payments, which we haven’t had before. And we’re going to be getting quite a reasonable amount of money to do what we’ve always done.

In order to get the money from the government, you have to tick a lot of boxes – luckily, being Stock-Free already puts you in that position. So if you want to go into Organic, you can receive over £400 per hectare from the government for conversion grounds, which is actually quite a good amount. If you have say, 1,000 hectares, this is serious money! So, there is potential for people to change.

What advice would you give farmers who want to transition to Stock-Free Organic farming, but don’t know where to start?

Firstly, you need to visit people who are already doing this. At my farm, we get a lot of visitors. We have a group of 30 coming in tomorrow! Visiting other farms is really important and getting in contact with people who’ve already done it.

You also need to consider the implications for the farm, and you need to have a conversion plan. And the difficult one is that you need to deal with the livestock you already have on the farm.

Currently, there aren’t many places for livestock to go and live out their lives – this again, is another fantastic opportunity for farmers. Most farmers with livestock don’t actually like having them slaughtered, that’s the bit they don’t want to talk about or deal with. But if someone came up with a plan for that, for example, to pay them to look after animals indefinitely, many farmers would be delighted to partake. That could be part of a whole package of grant support, which farmers could get. And I think the present support system for farmers could be used to advantage in that situation.

Most or many of these livestock farmers are losing money; they will be better off having no livestock. That’s how bad it’s got. So in that situation, if they did have livestock and somebody was supporting them through charitable means to care for them, then they would be in a much better place; they wouldn’t need to have a part-time job, as many farmers still do in order to support their farms. So, I think there are some fantastic opportunities for existing livestock farmers who wish to change the system to caring for animals rather than slaughtering animals.

And then, there are rural needs to have livestock in the countryside. Nothing like the numbers are now, and certainly not in factory farms – all factory farms have to go. But there is still a case to have some grazing livestock because there is a real value in terms of encouraging flora and fauna and biodiversity, and managing habitats. Animals have a role to play in that and the numbers would be very much reduced. And if they were being cared for, that would be a perfect solution to the existing crisis that has affected livestock farmers.

Our final question is, how can businesses and industry players support farmers in the transition to alternative protein foods?

It would be really down to a support mechanism to encourage farmers. If we want farmers to change there is no argument really about it – they will need money.

So, providing a farm had a credible plan to transition, then I think that would attract funding from certain areas of industry. We would have a vested interest in that happening, which is unfortunate – it’s sad that all of this is wholly or partly dependent on some financial support, but farmers are already reliant on that kind of help.

We just need to change the way that support goes. Personally, I would prefer that support comes from the central government – from public money and public support. But if there is some available support from industry for whatever reason it wants to do it – and we would need to analyze what the reasons for industry are in terms of supporting that – then yes, funding would be an extremely useful way to help farmers through that very difficult transition.

Thank you, Iain!

Iain Tollhurst has just been awarded an M.B.E for his services to organic agriculture, from His Royal Highness Charles III, King of the United Kingdom. ProVeg International congratulates Iain and thanks him for his efforts to promote sustainable food systems.

You can learn more about Tolhurst Organic, here.

To get in touch with the ProVeg team and develop your plant-based strategy, get in touch with us at [email protected].

References

- To label your product as organic in the UK, you must be registered with one of the UK organic control bodies in order to be certified. You can decide which control body to register with based on your location and business needs. Information from https://stockfreeorganic.net/stockfree-organic-services#organic. Accessed 2023-06/22.