The ‘food plate’ is endorsed by various nutrition societies and national governments and provides a simple guide to making healthy food choices. The composition of the food plate corresponds to current scientific knowledge regarding the health effects of what we eat and drink. In the following article, we present the plant-based food plate from ProVeg.

What is the plant-based food plate?

You may have heard about the food pyramid at school. The broad base of the pyramid represented the foods we should eat in large amounts. The pointed top shows the foods we should eat less of. Over the years, however, the approach to educating people about nutrition has changed. More and more nutrition societies worldwide now use a plate model instead of a pyramid.

The plate illustrates what proportion of each food group should be consumed per meal. The straightforward presentation in the form of a ‘healthy plate’ is intended to help consumers develop healthy eating habits more easily than with the pyramid model.

The ProVeg food plate helps anyone to plan a healthy plant-based meal whether they are following a flexitarian, vegetarian or vegan diet.

The following items belong on a healthy plant-based food plate

Mainly vegetables and fruit with every meal – 1/2 of the plant-based food plate

Fruit and vegetables are an important source of vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients, and fiber. When it comes to food choices, variety plays an important role, so eat the rainbow!

Likewise, more vegetables than fruit should be consumed – of the recommended five servings per day, three should be in the form of vegetables and two in the form of fruit.1 2

Wholegrain foods – 1/4 of the plant-based food plate

Wholegrain cereals such as oats, rye, spelt, wheat, barley, millet, and rice, along with pseudocereals such as quinoa, amaranth, and buckwheat, provide complex carbohydrates, fiber, and phytonutrients. They also contain important vitamins (especially B vitamins) and minerals (for example, iron, zinc, and magnesium). The quality of the carbohydrates you eat is at least as important as the quantity. Several studies show a link between whole grains and better health.3 4

Choose protein from plant sources – 1/4 of the plant-based food plate

The recommended daily intake of protein is a modest 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.5 A plant-based diet can provide a sufficient supply of protein if a broad selection of plant protein and a sufficient intake of calories is ensured. Among plant foods, the main sources of protein are pulses (lentils, peas, beans, and lupins) and pulse-based products such as tofu, tempeh, falafel, and plant-based milk and yogurt. Cereals (rice, oats, millet, wheat, spelt, and rye), pseudocereals (amaranth, buckwheat, and quinoa) as well as nuts, almonds, sesame seeds, hemp seeds, sunflower seeds, and chia seeds also contain particularly high proportions of protein.6 In moderation, plant-based burgers, sausages, and other meat substitutes can also be part of this group.7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 When looking for healthy options, keep an eye on hidden sugar as well as the amount of fat and salt.

By combining various plant proteins such as, cereals with pulses, the supply of all essential amino acids can be optimized. It is sufficient to eat the various sources of protein throughout the day, rather than during a single meal.15 16

A sufficient intake of water – 1.5-2.5 liters per day

The recommended amounts for total water intake include the moisture content of food and only apply with moderate temperatures and moderate physical activity levels. You should preferably drink water, non-caffeinated unsweetened tea, and other non-alcoholic, low-calorie beverages such as juice spritzers. In high temperatures or if you exercise, the amount of water you need may increase.17

Keep in mind that the absorption of iron and other nutrients can be inhibited by certain components of food, such as phytic acid or polyphenols. This means that coffee, black tea, and wine should not be consumed in conjunction with iron-rich foods.18

Choose foods with healthy fats

Total fat intake should not exceed 30% of total energy intake.19 It’s best to choose foods with unsaturated fats, to limit foods high in saturated fat, and to avoid trans fats. Healthy unsaturated fats can be found in nuts and seeds and cold-pressed oils made from them. Olive oil, rapeseed oil, sunflower, peanuts, soy beans, and avocados are all particularly good sources of unsaturated fatty acids. You can also add nut butters such as peanut, almond or cashew to your plate.

Palm and coconut oil, on the other hand, are rich in saturated fatty acids and should only be consumed in small amounts (less than 10% of total energy intake). Also, it is best to try to avoid trans-fats that are often found in fried foods and pre-packaged snacks such as frozen pizza or pies.20 21

Other important nutrients on the plant-based food plate

The consumption patterns of people who follow a plant-based diet are usually closer to the recommended daily amounts for the intake of protein, carbohydrates, and fat than for people who follow a conventional diet. In addition, the intake of dietary fiber and several micronutrients is often higher in a purely plant-based diet. However, there are also nutrients that people eating a plant-based diet need to pay special attention to.22 The following table provides an overview of these nutrients.

Table 1: Nutrient supply of plant-based diets

*critical in the general population

With every diet – whether flexitarian, vegetarian, or vegan – good planning is essential to avoid nutritional deficiencies. Optimal plant-based nutrition can be ensured by eating a balanced and varied diet while paying attention to critical nutrients. Nutritionists also recommend having a blood test done every year or two.

In the following section, we explain how to ensure your supply of critical nutrients.

Vitamin B12

Those eating little or no animal-based products should ensure a proper intake of vitamin B12 by taking dietary supplements in the form of, for example, tablets, drops, and/or using vitamin B12 toothpaste. Also, some processed plant-based foods are fortified with vitamin B12. These include various plant-based milks and yogurts, muesli, cornflakes, fruit juices, and some meat alternatives. Depending on the vitamin B12 content, uptake of B12 can be improved by consuming these fortified foods, but this will not always cover daily requirements.23 24

Calcium

Dairy products are often considered to be the main source of calcium, although sufficient quantities of calcium are also found in many plant-based foods. There are actually numerous reasons for favoring calcium from plants, because dairy products, while being a source of calcium, are also one of the top sources of saturated fat, sodium, and trans fats.25

It’s not just the amount of calcium we consume that is important, but its bioavailability: how easily the body can absorb the calcium from a specific source. The bioavailability of calcium from plant sources depends on the extent to which oxalates or phytates are present, since both inhibit the absorption of this mineral. Blanching, soaking, and sprouting are highly effective ways to reduce the number of oxalates and phytates in vegetables without negatively affecting the nutritional composition.26 27

Valuable sources of calcium include cruciferous vegetables, leafy greens, beans, sweet potatoes, almonds, sesame seeds and tahini, dried figs, algae, and mineral water, as well as fortified foods such as plant milks and tofu.

Zinc

The bioavailability of zinc is higher in animal-based foods than in plant-based and is influenced by various nutritional substances. The so-called anti-nutritional factors such as phytates contained in cereals and pulses, as well as oxalates contained in spinach and tea, have a particularly inhibiting effect on zinc bioavailability.

But the good news is that anti-nutritional factors can be significantly reduced by the use of traditional food preparation methods such as fermentation, germination, autoclaving, and soaking, as well as cooking.28 Moreover, citric acid, which is contained in citrus fruits and numerous other types of fruit, improves the availability of zinc from phytate-rich foods.

Valuable sources of plant-based zinc are tempeh (fermented soy beans), overnight oats (soaked oat flakes), quinoa, pumpkin seeds, lentils, and whole grain products.

Omega-3 fatty acids

Omega-3 fatty acids belong to the family of polyunsaturated fatty acids which are essential for our health. Linseed oil (also known as flax oil or flaxseed oil) has the highest content of Omega-3 fatty acids. Other foods rich in Omega-3s include rapeseed, olive, walnut, and hemp oil. It can also make sense to use microalgae oils, which are a good source of the long-chain Omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Ground flaxseed, walnuts and chia seeds can also contribute to the supply of Omega-3 fatty acids. It is recommended to include one of the following options (or a combination) in your daily diet: 5–10 walnuts, 1–2 teaspoons of cold-pressed flaxseed, 1–3 tablespoons of ground flaxseeds, 1–2 tablespoons of chia seeds, or 1–2 tablespoons shelled hemp seeds.29

Iodine

Historically, iodine deficiency has been a major problem worldwide. Since the early 1990s, international efforts have drastically reduced the incidence of iodine deficiency. However, it is still important to pay attention to your iodine intake – no matter what your diet looks like.30 In many countries, iodised table salt is nowadays an important source of iodine.31 32 Foods that have a naturally high iodine content are almost exclusively seafood and seaweed/algae.

However, there is a risk of adverse health effects when consuming very iodine-rich types of seaweed. With this in mind, consumption is not recommended if iodine content exceeds 20 mg/kg of the dry product.33 Seaweeds with moderate iodine content include nori, wakame, and dulse.34

Iron

Iron deficiency is the most common nutrient deficiency worldwide.35 Iron deficiencies can usually be counteracted by shifting to a healthy and varied diet and by regularly eating iron-rich foods such as whole grains including “pseudo-grains” such as amaranth, quinoa, and buckwheat, along with their products such as bread and pasta. In the nuts and seeds category, sesame seeds are the frontrunners, followed by sunflower seeds, pine nuts, and almonds. Pulses such as kidney beans, lentils, and chickpeas are also rich in iron. Certain methods of preparation (e.g. soaking or fermenting pulses, milling and baking cereals), as well as combining certain foods, are key to increasing iron absorption and thus reducing the risk of iron deficiency. To increase the intake of iron from plant sources, iron-rich foods should always be eaten together with foods containing vitamin C (e.g. lemons, limes, apples, orange juice, and peppers).36 37

Vitamin D

Sufficient levels of vitamin D can be achieved by sufficient bodily exposure to sunlight. In the summer months, it is assumed that about 5-30 minutes of sun exposure, especially between 10 am and 4 pm daily, on the face, arms, hands, and legs without sunscreen can normally lead to sufficient vitamin D synthesis.38 However, in the colder months, especially for people living in the northern hemisphere, vitamin D supplementation may be essential. Before taking any supplement, it is strongly advised to have appropriate blood tests and consult with a medical professional.

Depending on age, geographical location, dietary preferences, and skin color, a daily supplemental dose of 10–50 micrograms (400-2000 IU – IU means international units) of vitamin D may be needed to achieve optimal serum levels.39 Because it’s difficult to suggest a specific dosage that works for everybody worldwide, each country has its own suggested daily dosage. An overview can be found in our article on vitamin D.

Can processed foods be part of a healthy sustainable diet?

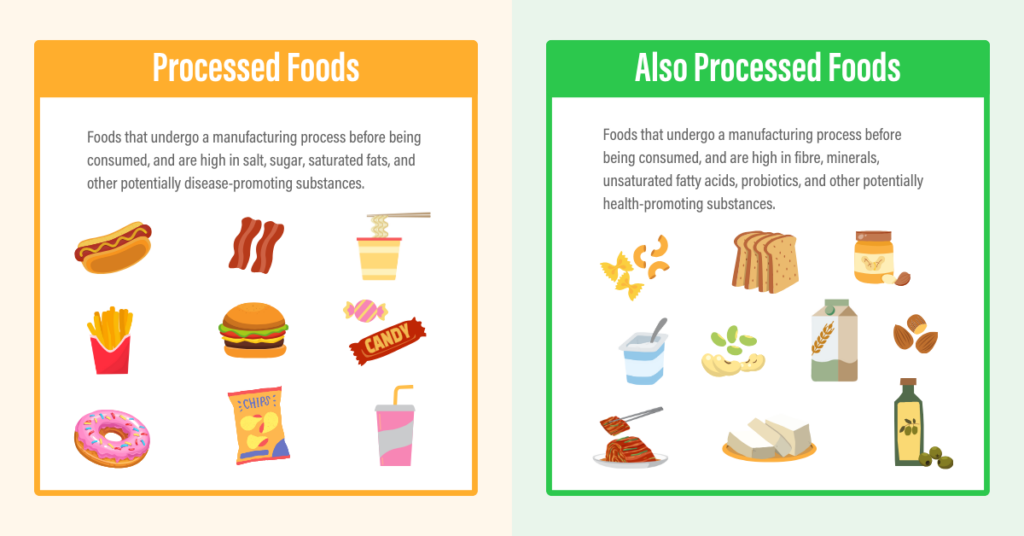

Yes, they can! Food processing has been an integral part of human diets for millennia and plays a crucial role in providing safe and convenient food options. The degree of processing alone cannot be used to make a reliable statement about the health value of food. Whole-wheat bread for example, which is commonly seen as a healthy, “natural” food, belongs to the processed/ultra-processed categories that nowadays are mostly considered negative. You can find more examples in the graphic below.

When you are looking for healthy options, keep an eye on hidden sugar, as well as the amount of saturated fat and salt, especially when it is added during processing. These are the ingredients that cause many health problems – not the processing itself. Being tasty, convenient and storable, processed foods make up a large part of many people’s diets. Reformulating them by reducing their sugar, salt, and saturated fat content therefore offers a great opportunity to improve public health.40

A team of researchers from the US Department of Agriculture recently published a study showing that it is possible to have a healthy balanced diet even with the consumption of ultra-processed foods. They found that it is possible to design a healthy diet in which 91% of calories come from ultra-processed foods (as classified by the NOVA system) and still meet the official Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommendations. This shows once again that the degree of processing is not always a good predictor of the healthiness of a product.41

Table 2 shows our own example of a single day of plant-based eating, based on an average caloric diet of 2000 kcal and using processed and ultra-processed foods.

Table 2: Menu for one day using processed and ultra-processed foods

Five key messages for a well-planned plant-based diet:

- Eat the rainbow and incorporate a wide variety of fruits and vegetables. Add them to every meal. Vitamin C from fruits and vegetables can promote the absorption of numerous nutrients

- Eat wholemeal products and pulses every day. Use traditional food preparation methods such as fermentation, germination, autoclaving, soaking, as well as cooking, to increase the bioavailability of nutrients.

- Including fortified foods, such as calcium-fortified plant-based milk, in one’s diet can prove useful in following a plant-based diet. Those eating little or no animal-based products should ensure a proper supply of vitamin B12 by taking dietary supplements.

- Processed foods can be part of a healthy sustainable diet. The degree of processing alone cannot be used to make a reliable statement about the health value of food. Wholemeal bread, which is commonly seen as a healthy, ‘natural’ food, belongs to the processed/ultra-processed categories that are nowadays mostly considered negative.

- Keep an eye on added sugar, as well as the amount of saturated fat and salt. These ingredients should be minimized in the diet.

References

- Harvard T. H. Chan (2018): Vegetables and Fruits. Available at https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/vegetables-and-fruits/ [19.07.2024]

- British Dietetic Association (2020). Fruit and vegetables – how to get 5-a-day. Available at: https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/fruit-and-vegetables-how-to-get-five-a-day.html [19.07.2024]

- Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., et al. (2019) Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. The Lancet, 393, 447-492.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4 - Harvard T. H. Chan (2024): Whole Grains. Available at https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/whole-grains/ [19.07.2024]

- Harvard Health Publishing (2023): How much protein do you need every day?. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/how-much-protein-do-you-need-every-day-201506188096#:~:text=The%20Recommended%20Dietary%20Allowance%20(RDA,meet%20your%20basic%20nutritional%20requirements. [19.07.2024]

- Langyan, Sapna et al.(2022): Sustaining Protein Nutrition Through Plant-Based Foods. Frontiers in nutrition vol. 8 772573. doi:10.3389/fnut.2021.772573

- Clark M, Springmann M, Rayner M, Scarborough P, Hill J, Tilman D, Macdiarmid JI, Fanzo J, Bandy L, Harrington RA. Estimating the environmental impacts of 57,000 food products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Aug 16;119(33):e2120584119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2120584119. Epub 2022 Aug 8. PMID: 35939701; PMCID: PMC9388151.

- Ritchie, H., Reay, D. S., & Higgins, P. (2018). Potential of Meat Substitutes for Climate Change Mitigation and Improved Human Health in High-Income Markets. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2018.00016

- PLANT-BASED MEAT: A HEALTHIER CHOICE? A comprehensive health and nutrition analysis of plant-based meat products in the Australian and New Zealand markets Available at: https://www.foodfrontier.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2020/08/Plant-Based_Meat_A_Healthier_Choice-1.pdf

- Smetana, S., Profeta, A., Voigt, R., Kircher, C., & Heinz, V. (2021). Meat substitution in burgers: Nutritional scoring, sensorial testing, and Life Cycle Assessment. Future Foods, 4, 100042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fufo.2021.100042

- Melville, H, Shahid, M, Gaines, A, et al. (2023): The nutritional profile of plant-based meat analogues available for sale in Australia. Nutrition & Dietetics. 2023; 80(2): 211-222. doi:10.1111/1747-0080.12793

- Craig W.J. & U. Fresán (2021 ): International Analysis of the Nutritional Content and a Review of Health Benefits of Non-Dairy Plant-Based Beverages. Nutrients. Mar 4;13(3):842. doi: 10.3390/nu13030842. PMID: 33806688; PMCID: PMC7999853.

- Alessandrini, R., Brown, M. K., Pombo-Rodrigues, S., Bhageerutty, S., He, F. J., & MacGregor, G. A. (2021). Nutritional Quality of Plant-Based Meat Products Available in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients, 13(12), 4225. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124225

- Rodríguez-Martín, N. M., Córdoba, P., Sarriá, B., Verardo, V., Pedroche, J., Alcalá-Santiago, Á., García-Villanova, B., & Molina-Montes, E. (2023). Characterizing Meat- and Milk/Dairy-like Vegetarian Foods and Their Counterparts Based on Nutrient Profiling and Food Labels. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 12(6), 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12061151

- Dimina, Laurianne et al. (2022): Combining Plant Proteins to Achieve Amino Acid Profiles Adapted to Various Nutritional Objectives-An Exploratory Analysis Using Linear Programming. Frontiers in nutrition vol. 8 809685. doi:10.3389/fnut.2021.809685

- Christian Koeder & Federico J. A. Perez-Cueto (2022): Vegan nutrition: a preliminary guide for health professionals, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2107997

- Harvard Health Publishing (2023): How much water should you drink? Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/how-much-water-should-you-drink [19.07.2024]

- Ems T. et al. (2020): Biochemistry, Iron Absorption. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448204/ [19.07.2024]

- WHO (2020): Healthy diet. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet [19.07.2024]

- WHO (2020): Healthy diet. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet [19.07.2024]

- Harvard T. H. Chan (2024): Fats and Cholesterol, Available at https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/what-should-you-eat/fats-and-cholesterol/ [19.07.2024]

- Christian Koeder & Federico J. A. Perez-Cueto (2022): Vegan nutrition: a preliminary guide for health professionals, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2107997

- Christian Koeder & Federico J. A. Perez-Cueto (2022): Vegan nutrition: a preliminary guide for health professionals, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2107997

- National Institute of Health (NIH) (2024): Vitamin B12, Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available at https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB12-HealthProfessional/ [19.07.2024]

- WHO (2020): Healthy diet. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet [19.07.2024]

- Maciej S. Buchowski, 2015. “Calcium in the Context of Dietary Sources and Metabolism”, Calcium: Chemistry, Analysis, Function and Effects, Victor R Preedy

- Samtiya, M., Aluko, R.E. & Dhewa, T. (2020): Plant food anti-nutritional factors and their reduction strategies: an overview. Food Prod Process and Nutr 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43014-020-0020-5

- Samtiya, M., Aluko, R.E. & Dhewa, T. (2020): Plant food anti-nutritional factors and their reduction strategies: an overview. Food Prod Process and Nutr 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43014-020-0020-5

- Christian Koeder & Federico J. A. Perez-Cueto (2022): Vegan nutrition: a preliminary guide for health professionals, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2107997

- National Institute of Health (NIH) (2024): Iodine, Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available at https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iodine-HealthProfessional/ [19.07.2024]

- WHO (2023): Iodization of salt for the prevention and control of iodine deficiency disorders. Available at https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/salt-iodization [19.07.2024]

- UNICEF (2024): Iodine. Available at https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/iodine/ [19.07.2024]

- Nicol, K., Nugent, A. P., Woodside, J. V., Hart, K. H., & Bath, S. C. (2023). Iodine and plant-based diets: A narrative review and calculation of iodine content. The British Journal of Nutrition, 131(2), 265-275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114523001873

- Christian Koeder & Federico J. A. Perez-Cueto (2022): Vegan nutrition: a preliminary guide for health professionals, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2107997

- WHO (2020): WHO guidance helps detect iron deficiency and protect brain development. Available at https://www.who.int/news/item/20-04-2020-who-guidance-helps-detect-iron-deficiency-and-protect-brain-development#:~:text=Iron%20deficiency%20is%20the%20main,and%2042%25%20of%20children%20worldwide. [19.07.2024]

- Christian Koeder & Federico J. A. Perez-Cueto (2022): Vegan nutrition: a preliminary guide for health professionals, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2107997

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2016): Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. Available at https://www.eatrightpro.org/-/media/eatrightpro-files/practice/position-and-practice-papers/position-papers/vegetarian-diet.pdf [19.07.2024]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2023): Vitamin D – Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available at https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/ [19.07.2024]

- Pludowski P, Holick MF, Grant WB, Konstantynowicz J, Mascarenhas MR, Haq A, Povoroznyuk V, Balatska N, Barbosa AP, Karonova T, Rudenka E, Misiorowski W, Zakharova I, Rudenka A, Łukaszkiewicz J, Marcinowska-Suchowierska E, Łaszcz N, Abramowicz P, Bhattoa HP, Wimalawansa SJ. Vitamin D supplementation guidelines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018 Jan;175:125-135. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.01.021. Epub 2017 Feb 12. PMID: 28216084.

- Onyeaka, Helen et al. (2023): Global nutritional challenges of reformulated food: A review. Food science & nutrition vol. 11,6 2483-2499. 6 Mar. 2023, doi:10.1002/fsn3.3286

- Hess, J. M., Comeau, M. E., Casperson, S., Slavin, J. L., Johnson, G. H., Messina, M., Raatz, S., Scheett, A. J., Bodensteiner, A., & Palmer, D. G. (2023). Dietary Guidelines Meet NOVA: Developing a Menu for A Healthy Dietary Pattern Using Ultra-Processed Foods. The Journal of Nutrition, 153(8), 2472-2481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.06.028